NSX Packet Walks

by vAntMet

I was once asked an interview question that was a very simple question with an interesting answer: How does a switch pass packets.

I’m going to start in this blog post, with that question, but in a virtual environment. Then I’m going to extrapolate to a couple of NSX situations that I find quite interesting.

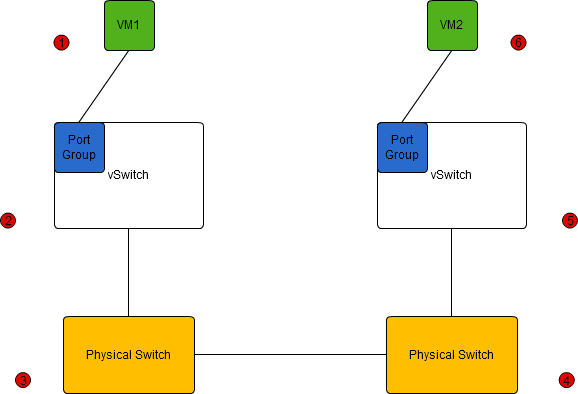

The above diagram shows two VMs on the same VLAN. The vSwitches can be standard or distributed, and the physical switches could be anything from a desktop unmanaged switch through to a Nexus. For our purposes, that doesn’t matter.

The two VMs boot. The have a mac address (Layer 2), and an IP address (Layer 3) preconfigured. Just for fun we’ll assume they each have the IP address of the other in their hosts file, so we don’t have to involve DNS. VM1 wants to send a packet to VM2.

- VM1 knows the IP address of VM2, and knows that it is on the same subnet (so will not send the packet to the default gateway). It does not know the MAC address of VM2 though. So VM1 sends an ARP packet to FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF, the Layer 2 broadcast address. This is passed via the portgroup into the vSwitch. The vSwitch at this point stores VM1’s MAC in it’s CAM Table and IP addresses in it’s fib table.

- the vSwitch passes the packet to the physical switch. The physical switch stores the IP and MAC of VM1 along with the port the packet entered on.

- the first physical switch passes the broadcast traffic out of all ports, but stores where the request came from in their tables.

- the second physical switch passes the broadcast traffic out of all ports, but stores where the request came from in their tables.

- the second vSwitch switch passes the broadcast traffic out of all ports, but stores where the request came from in their tables.

- VM2 sees the request and replies. In this case the destination MAC is known, so the packet is passed back through the steps in reverse order. At each step the physical and virtual switches store the MAC address of VM2 to the CAM table, and pass the packet out of a single port, back toward VM1.

This is about the simplest conversation that can happen over a switched Ethernet network.

Now let’s step it up a gear.

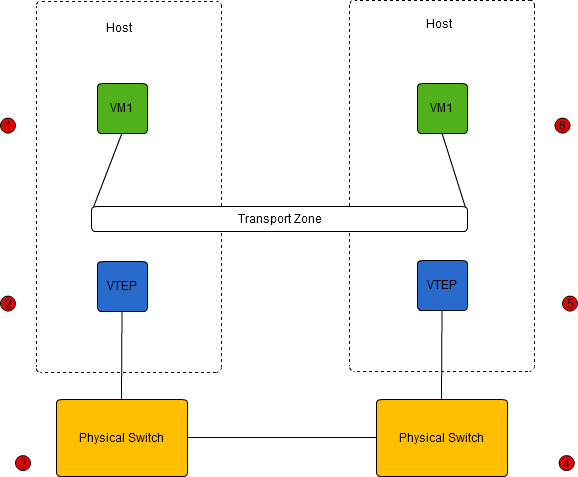

Here we have a very simple, NSX based network. I am assuming one transport zone, set to “unicast mode”, with one logical network (say VXLAN 5001) which both VMs are attached to. In this case, each host on boot, is notified of other hosts int eh transport zone, and a tunnel is negotiated between the hosts. This tunnel is terminated at a VTEP or Virtual Tunnel End Point, within the ESX kernel.

One of the key differences between Unicast Mode and the other modes is that, in unicast mode, the host relays the IP information for the VM to the controllers which then relay that information to the vDistributed Switches that make up the Logical Switch. This means that when the ARP is generated at 1. The host already knows the IP/MAC combination of VM2. The full flow goes like:

- VM1 sends an ARP packet to FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF. This is passed to the local dvSwitch and into the VTEP.

- The VTEP encapsulates the ARP into a VXLAN packet with the destination mac address being the VTEP mac address of the host VM2 is running on, and the source address being it’s own TEP MAC address. This packet is pushed out to the physical switch.

- In normal circumstances the physical switches will have the VTEP MAC addresses through communication with the controller, and tunnel initiation, but if not, this is identical to the first scenario, except the VTEP MAC addresses are used, not the VM addresses.

- The second physical switch acts again just like it did last time.

- The VTEP de-encapsulates the packet, and passes the original ARP into the dvSwitch.

- Packet is delivered to the VMs on that VLAN on that host, and VM2 responds.

In both scenarios our VMs have both sent and received the same information. Notice how the MAC address of the VMs is never seen by the switches though in our second case. This means we’ve just reduced the CAN and fib tables on the switches by a couple of orders of magnitude. By not having to have the hundreds of MAC addresses and IP addresses for the hosts the switches can have much smaller, and much more efficient CAM and FIB tables. This is not likely to be an issue for the average enterprise network, but it can help service providers with thousands of VMs in their farms.

In the next post I will continue with situations that involve routing.

tags: vmware - nsx